In October 2016, two exhibitions were inaugurated in Cairo and Paris respectively, commemorating an Egyptian surrealist art and literature group, Art et Liberté.

I.

Art et Liberté was co-founded by surrealist author Georges Henein in 1939. At the advent of World War II, artists and writers rallied around Henein and painter and writer Ramses Younan in their call for a perpetual revolution in art. The group aimed at gearing public opinion in Egypt away from the notion of modernization—regarded as a product of western imperialism—towards that of modernity, which saw art and daily life as malleable in their constant potential for improvement, “dans la mêlée,” as Henein called it.

On 22 December 1938, a tract in French and Arabic was distributed on the streets of Cairo, and sent out around the world. Vive L’Art Dégénéré denounced the Nazi condemnation of modern art as degenerate “and ripe for the bonfire,” to quote poet Abdel Kader Al Janabi. Forty self-proclaimed artists, writers, journalists, and lawyers signed the manifesto, including foreigners fleeing war-torn Europe and Egyptians alike, towards an international solidarity movement: “[…] We stand for this degenerate art. It is in it that reside all the chances of the future. Let us work for its victory over the middle ages rising in the very heart of Europe […].” Printed alongside a reproduction of Picasso’s Guernica, the text in French and Arabic was probably written by Georges Henein. The name Art et Liberté alluded to André Breton and Léon Trotsky’s manifesto For an Independent Revolutionary Art, signed with Diego Rivera in Mexico earlier the same year.

Throughout the war years, Art et Liberté published books, held lectures, hosted literary salons, and apparently some wild parties at La Maison des Artistes. They organized five yearly group exhibitions under the title Expositions de l’Art Independent, held in what were considered unusual spaces at the time in downtown Cairo. [1] The following description by Al Janabi is telling of their spirit: “The five exhibitions of Independent Art were very large and have certainly left their traces on the history of modern Egyptian art, for they were very provocative and full of humour noir and spectacular. They contained all sorts of paintings, photographs, sculptures and ready-made objects." [2]

II.

In October 2016, two travelling exhibitions were inaugurated, a few days apart, jointly forming the largest recreation to date of Art et Liberté’s five Expositions de l’Art independent (1940-45). In Cairo, From Art to Liberty was co-curated by the Sharjah Art Foundation at the Palace of the Arts, and Art et Liberté: Rupture, War and Surrealism in Egypt (1938-1948) was inaugurated at the Centre Pompidou in France, five years plus in the making by curator-duo Sam Bardaouil and Till Fellrath. The exhibitions showcased hundreds of artworks and archival documents, many of which were uncovered for the first time since the 1940s.

In a recent review, art critic Isma’il Fayed compares the lists of collections that make up each show. Considering the many rare pieces displayed to the public for the first time, the exhibitions indeed highlight a particularly underexplored moment in the history of modern art in Egypt. Fayed in turn questions if “we’re seeing a bidding war between two of the region’s largest culture patrons, the UAE and Qatar, for prestige, capitalist enlightenment and progress.” Indeed, we have witnessed in recent weeks, a rapid boom in the Arab modern art market, notably with increased record sales at global auction houses stationed in the Gulf countries. Last month, Mahmoud Sa’id’s Assouan – Nile et dunes, at the top of Christies record sale list, sold for $685,500, a few days before the first catalogue raisoné for Said, and any Arab artist, was launched at Christie’s Dubai. Said reached another record sale at the more recent Sotheby’s Orientalist and Middle Eastern sale in London, when his portrait of Mme. Batatouni Bey was acquired for $502,916. Both Sotheby’s and Christie’s seem optimistic about boosting the regional art market, highlighting perhaps the timely convenience of the concurrent exhibitions. Gallerist Fatenn Mostafa Kanafani more optimistically points to the urgency of the exhibitions on Art et Liberté, describing them as the “first substantial surveys on the Egyptian surrealists since 1987 [which] aim to position avant-garde Egyptian art as part of the narrative of global modernity.” In 1987, Abdel Kader Al Janabi presented his lecture The Nile of Surrealism at a conference at the University of British Columbia. A year prior, Samir Gharieb had published Surrealism in Egypt and the Plastic Arts. Mostafa’s comment alludes to a gap in scholarly research on the history of surrealism in Egypt since these singular efforts of the 1980s.

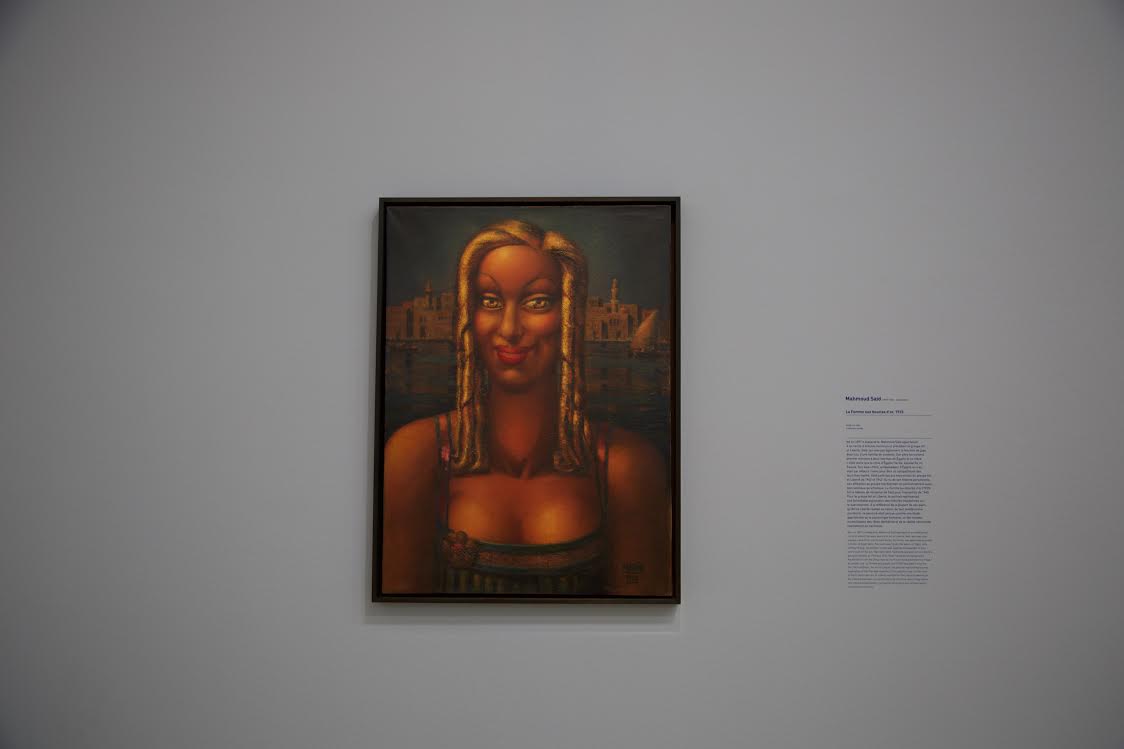

[Mahmoud Said, La Femme aux Boucles d`Or (1933)]

[Mahmoud Said, La Femme aux Boucles d`Or (1933)]

A revived interest in the movement was sparked by the research of Adam Broomberg and Oliver Chanarin during their residency at the Townhouse Gallery in Cairo in 2010. As part of their exhibition, they produced The Prestige of Terror—a film on the inner workings of a mid-century printing press, which would have been used by Art et Liberté at the time. Broomberg and Chanarin also founded a website, a public domain archive with primary and secondary sources on surrealism in Egypt, run by the Townhouse Gallery. Art historian Anneka Lensen describes a recent revival of interest in Art et Liberté as one that “arises not from academia per se, but out [of] the art world of galleries, museums and auction houses.” A lack in substantial research over the years is recently coupled with a growing commercial interest. This speaks perhaps to the significant role played by collectors in the region on the accessibility of primary scholarly material for academics and researchers. Private patronage is undoubtedly the largest driving force in the preservation, restoration, and partial distribution of primary historical documents. The hope is that a growing commercial interest will inspire an institutionalization and democratization of collections in the near future.

In 2013, I worked with curator Sam Bardaouil in conducting primary research for his monograph Surrealism in Egypt: Modernism and the Art & Liberty Group (I.B. Tauris), published alongside the exhibition Art et Liberté: Rupture, War and Surrealism in Egypt (1938-1948). At Centre Pompidou, the exhibition coincided with two shows on French surrealists: René Magritte--La Trahison des Images (René Magritte—Treason of Images), and André Breton, which specifically sought to highlight the international dimension of Breton’s surrealism.

In the context of Pompidou, Bradaouil and Fellrath’s exhibition highlighted Art et Liberté’s role as active catalysts in the evolution of the formal “qualities of surrealism at the time,” as noted in the exhibition catalogue. The show coincides more broadly with a global concern in revisiting simplistic notions of central and peripheral modernisms. To curate an exhibition on Art et Liberté is to suggest a disruption “in the reading of the overall canon of Surrealism,” to use Bardaouil’s words.

III.

“Surrealism was an attempt at altering reality, and to change reality is an act of anarchy […]”

The voice of Anwar Kamel, founding member of Art et Liberté, resonates in colloquial Egyptian Arabic at the entrance of the fourth floor gallery at Pompidou:

[…] It was George Henein who drove the formation of a surrealist art group in Egypt, and during that time he was in contact with the surrealist movement in Paris and perhaps also with the Trotskyite movement. When the manifesto was presented to me, I agreed to it and signed it among the other signatories.

A recording from May 1990 of one of the last remaining voices from Art et Liberté, months before his death, resounds eerily throughout the gallery space. Across from the entrance, a silent projection shows King Farouk of Egypt unveiling Mahmoud Mokhtar’s public sculpture of Saad Zaghloul in Alexandria in 1937. The disparity of sound and image mirrors a political confrontation at its height at the advent of the second world war. In an already ruptured political environment, a generation of young avant-garde artists, writers, and journalists called for a revolt against a local bourgeoisie, supported by the royal family and in control of art patronage and literary censorship.

The suggested disparity becomes a backdrop against which the exhibition presents itself. Art et Liberté emerged amid the rising tension in the years leading up to the Free Officer’s coup in 1952. Under British mandate, Egypt participated in the war alongside the allies. While the Nazis never reached Cairo, the war gave way for political and paramilitary collectives to strengthen their activities in the public sphere.

[Hassan El Telmissany, Untitled (1946). Photograph by the author]

[Hassan El Telmissany, Untitled (1946). Photograph by the author]

In March 1938, Alexandria-born Italian futurist poet Filippo Tommaso Marinetti was invited to present a lecture in Les Essayistes club, of which Georges Henein was a member. Henein violently disrupted the lecture denouncing the products of Fascism, causing a scandal in the club, and eventually moving away “with the intention of establishing his own independent group,” according to Al Janabi. Bardaouil describes this event as “an uncompromising rejection of any alignment between Fascism, nationalism and art,” he considers it foundational in the birth of the Egyptian art movement.

At Pompidou, the exhibition unfolds in eight chapters sprawled onto nine gallery spaces—the title of each devised from a concept penned by members of Art et Liberté. At first glance, the exhibition layout invokes the group’s influence on the next generations of painters and art photographers in Egypt. A section is named after the “Contemporary Art Group,” founded by Abdel Hady El Gazzar, Hamed Nada, Samir Rafie, Rateb Seddik, etc. They are known today as a pioneering generation in modern Egyptian painting, and their works are the most collected among Egyptian artists. The exhibition suggests a lineage, a passing of the baton, between the 1940s and 1950s, highlighting Georges Henein’s reservations, nonetheless, with regard to the younger generation, whom he feared was becoming too nationalistic.

At Pompidou, countless pieces were unveiled after decades of sitting in private collections—as if given a second life. Rare finds included Mahmoud Said’s La Femme aux Boucles d’Or [pictured above], thought to have been lost for several decades until it was dug up from an anonymous collection in Alexandria. La Femme aux Boucles d’Or originally hung at the inaugural Exposition de l’Art Independent in 1941 as an homage to Said for his distinct figurative language—Georges Henein considered him a precursor to Art et Liberté. Paintings and photographs by lesser known members of the group were on view for the first time, Italian anarchist Angelo de Riz, Armenian photographers Ida Kar and Hassia, Eric de Nemès, and Ezeckiel Baroukh to name a few.

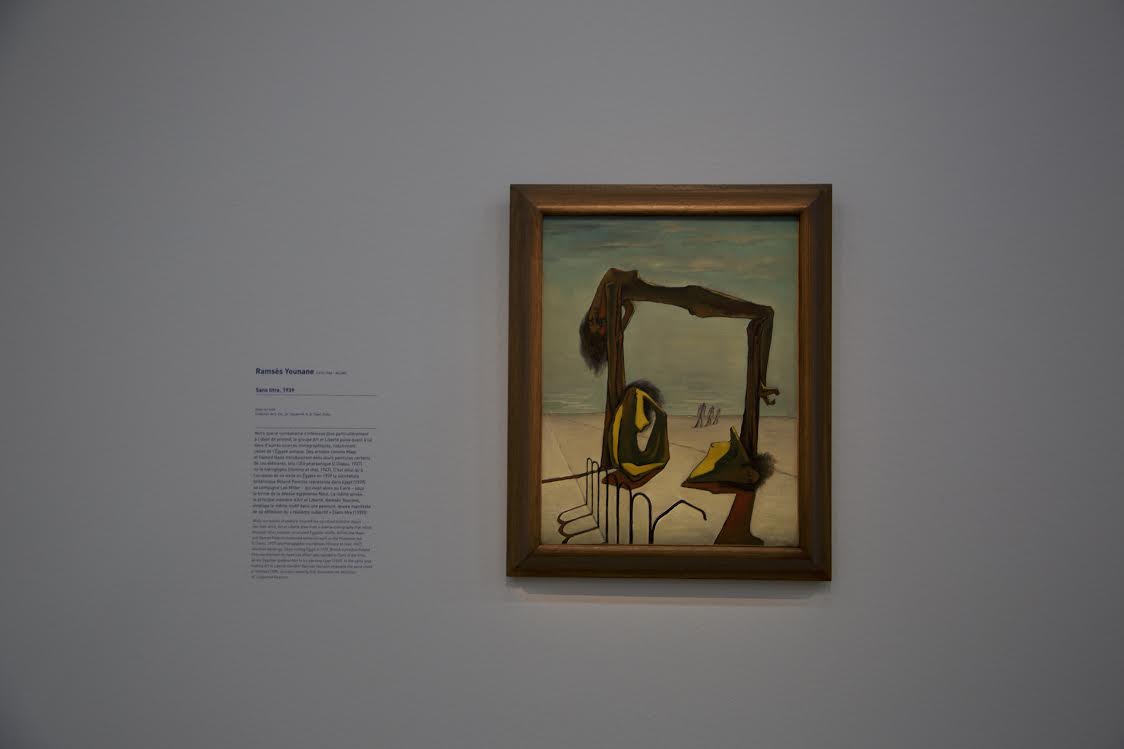

The section “Subjective Realism” particularly stood out. An iconic Ramses Younan oil painting, Untitled, from 1939 hangs alongside Egypt by Roland Penrose from the same year. Both works adopt the iconography of an ancient Egyptian goddess, Nut, mother of Isis and goddess of the sky, in a modernist painterly manner. Younan’s piece recalls Dalí’s and de Chirico’s desert landscapes.

[Ramses Younan, Untitled (1939). Photograph by the author]

[Ramses Younan, Untitled (1939). Photograph by the author]

In a vast arid desert, under a pale blue sky, three gray characters walk away in the background. A distorted female figure hangs by her limbs over the middle of the canvas. On the ground underneath the woman lay what may be two versions of her. One crouched in a familiar position, resting her head on her absent hand, and another broken limbed torso seems to have rolled beneath the dangling feet of Nut. In the foreground a fence denotes perspective, next to which the figure’s shadows are cast in blood red. “Subjective Realism” emphasized Art et Liberté’s break from European Surrealism. Younan aimed to create a pictorial language that intermeshed social symbols with a painterly method driven by subconscious impulses. After the war, many of the movement’s foreign members who were settled in Cairo began to emigrate. And by the 1950s, police crackdowns and increasing censorship drove many of the remaining Egyptians out as well.

Throughout my visit at Pompidou, I found myself wondering what Henein, Younan, De Riz, et. al. would have thought of their work hanging in the world’s most distinguished museums. Would Henein have found a reason to rebel as he once did against Marinetti? Perhaps, they would have found it amusing nonetheless, that after decades of oblivion, when an ironic twist of fate brought them back into attention, not one, but two exhibitions were held simultaneously to commemorate the life and death of Art et Liberté.

_________________________________

Footnotes

[1] Originally, Henein seemed to gear away from the national galleries and exhibition spaces available at the time. Instead he held the group’s five exhibitions at unusual spaces, namely the basement of the Lycée Français du Caire, the mezzanine level of the Immobilia building, the hotel Continental in downtown Cairo, and the Nile Club, long forgotten since, possibly out of a lack of other options but more importantly illustrating his overt disdain of the academic salon aesthetic.

[2] Al Janabi, Abdel Kader, “The Nile of Surrealism”, paper read on 26 September 1987 at the conference: The triumph of pessimism, University of British Columbia, Vancouver. The full text can be found at http://www.egyptiansurrealism.com/index.php?/contents/the-nile-of-surrealism/